The Sight of Stonehenge

Stately ships lay moored quietly as dusk softly settled on the docks of London. The air was wet with the smell of the sea, the buildings slowly receeding into the shadows of the night. Interiors beckoned with cozy warmth, the orange yellow glow of welcoming taverns lined up to face the sailors coming in from the ocean. At one, a certain seasoned italian captain paused a moment to take in the view before plunging through a doorway to the welcoming farmiliarity of his favorite establishment.

The man was known as diUmbria, the fabled Venetian sailor known far and wide as much for his bravery at sea and in battle as his pursuit of scientific advancement. He had just returned from Antwerp across the channel, where he had been making observations of a certain Dutch painting for a client. The art in question featured an imaginative portrayal of sea monster, inspired by tales of saliors of distant, foreign seas. Where fact and fiction met and divided, diUmbria had come to have great interest; just from the things he knew he’d seen in the wilderness, he knew there must be much more beyond his knowing.

Much to this end, he had gathered a group of colleagues to London to venture together and investigate a curiousity supposedly residing in the countryside somewhere to the west. The ancient ruins of what would have been concentric circles of massive stones lay there, the mysterious creation of a people long gone from history. The Venetian hoped to study the stones himself and, if unable to delve into their meaning any further, at the very least experience the presence of the artifacts first-hand. When he first heard of the stones he had in rushed off, sailed four days around the coast past Dover, made landfall in the pleasant rolling country of rich summer green. Only steps in, though, he had a change of heart; this was an adventure better taken in the presence of friends. So they gathered here, each a curious heart, to lay out the practicals of such a journey over steins of local ale before a heartily roaring hearth.

Two of his colleagues stood apart from the others, whether more in character or form it was difficult to say. Both were youths compared with the aged diUmbria. The first, Juan Garrion el Octavo, was a wealthy young Spaniard who would not shy away from being labelled as a pirate. With the sharpest eye for business in all the realms, Juan Garrion had quickly amassed a massive fortune well in advance of his elder friend. With most of his time spent at the markets in Seville, Juan had not seen a fraction of the globe with respect to diUmbria; but he was still quite capable at sea, and his wealth set him at the wheel of the finest vessels on the open waters. It was no secret that he had furnished diUmbria with some of his own ships, including the massive trading carrack dubbed The Joy of Triton, which the elder Venetian now helmed. The other was polar opposite in every respect; a young Englishwoman by the name of Marihelen. She had barely put to sea, but when she had her bravery and courage out to shame many a sailing man. Moreover, her heart was bound to science; ever was a textbook at her side where many held a saber, and every voyage served to add to ever-growing knowledge of academic pursuits from archaeology to astronomy, zoology to geology.

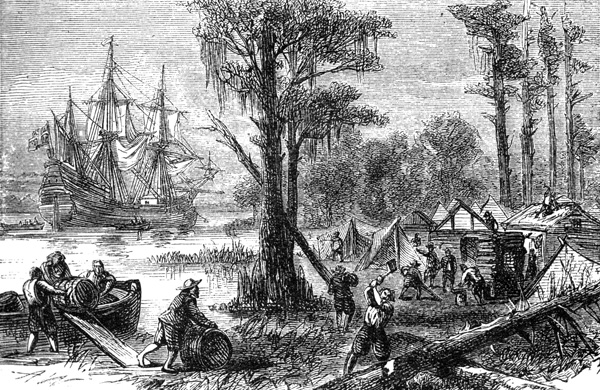

South they sailed, but as they passed the promontory of the cliffs of Dover, Juan Garrion went one way, while diUmbria the other, with Marihelen much confused between the two. The Venetian captain was a near infallible navigator, well known among his peers and academians of the age, and soon all fell behind his lead. The old Italian was endlessly perplexed at how others could get lost on the simplest journeys; for him, who had sailed to the very ends of the known world, the world was an open map to be read. Without further event they soon came to the planned landing area, moored in the open ocean, and the relevant people bore their small piloted craft to the shore.

Once ashore, all were shocked at how instantly wild the landscape became. Far from the civilized cobblestones of London, this was wild England in a nearly primeval state, lawless and wild. The concern for brigands and vagabonds was real; and indeed, they did appear as the group made their way north from the landing. No matter; the seasoned hands were quick to show enemies to the ends of their lives, and the party travelled forth regardless of local hostilities. Eventually the trio became separate from the others, and came to a lightly worn parth leading through a narrow pass to a hilltop where, behold, the monement itself lay bare. Imagine the surprise, then, when by some force unknown, only the old Venetian was allowed to go forward. The two others felt themselves born back by some invisible force. Jaun Garrion was at the limits of his frustration, as he was used to nearly limitless power on land and sea; Marihelen was more accustomed to obstacles, and calmly bent her intellect to discovering a way past this impedence.

diUmbria approached slowly around the silent monoliths and circled inward along the ancient lines, spiraling inward towards the center. Here he stood in gathering twilight, not quite dark enough to light a torch but dim enough to see the shade of the moon. Was it a trick of the light, then, or what did he see, but a sort of shimmering at the very center? It called to him, but when he went to it, unsure of what he saw, it vanished. He would always question, in the seconds afterward and to the end of his days, what he saw there, and whether it had really happened. In just a few moments hence, the other members of his group found their shackles gone, their freedom regained, and diUmbria was left forever wondering just what had happened to him at the center of Stonehenge that evening.